Medical Disclaimer: This is educational content only, not medical advice. Consult a licensed healthcare provider for diagnosis/treatment. Information based on sources like WHO/CDC guidelines (last reviewed: 2026-02-13).

This article is being expanded for more depth. Check back soon!

Mitral Valve Prolapse Comprehensive Guide Symptoms Diagnosis Management MCQs

Frequently Asked Questions

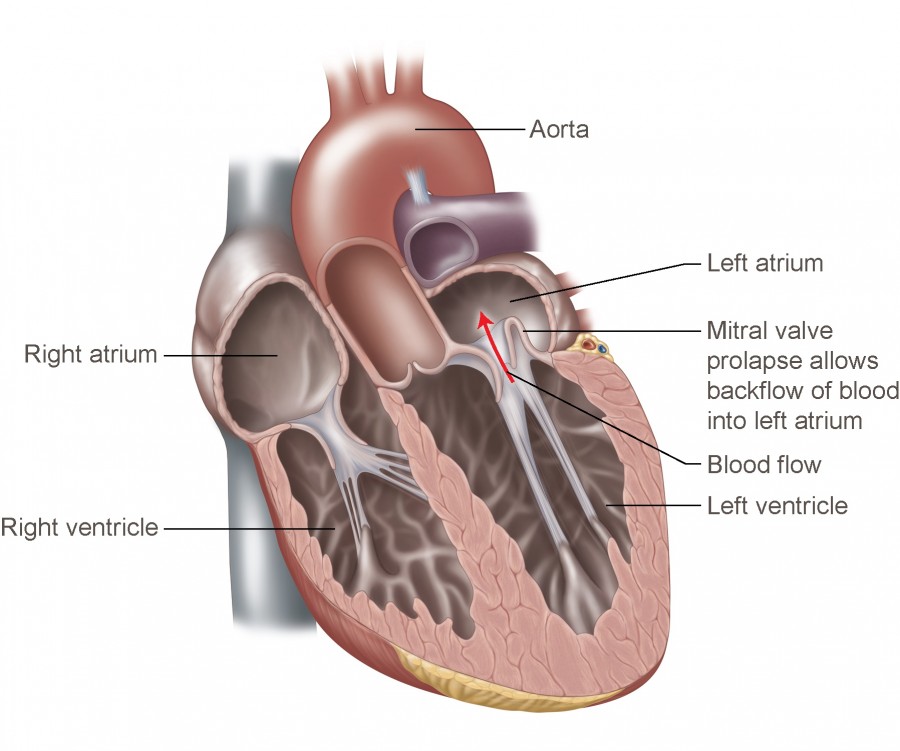

Mitral valve prolapse is a cardiac valvular disorder in which one or both mitral valve leaflets abnormally billow into the left atrium during systole, often due to myxomatous degeneration, and may be associated with mitral regurgitation.

The most common cause is myxomatous degeneration of the mitral valve leaflets. It may also be associated with connective tissue disorders such as Marfan syndrome, Ehlers–Danlos syndrome, rheumatic heart disease, ischemic papillary muscle dysfunction, or trauma.

Most patients are asymptomatic. When present, symptoms include palpitations, atypical chest pain, dyspnea on exertion, fatigue, dizziness, anxiety, and occasionally syncope.

The hallmark clinical sign is a mid-systolic click, often followed by a late systolic murmur if mitral regurgitation is present.

Standing or performing the Valsalva maneuver decreases left ventricular volume, causing the murmur and click to occur earlier and become louder, while squatting increases left ventricular volume and reduces the murmur.

Echocardiography is the gold standard for diagnosis. It demonstrates systolic displacement of the mitral valve leaflets into the left atrium and assesses leaflet thickness and severity of mitral regurgitation.

Classic mitral valve prolapse has leaflet thickness of 5 mm or more and carries a higher risk of complications, whereas non-classic prolapse has thinner leaflets and is usually benign.

Complications include progressive mitral regurgitation, atrial fibrillation, infective endocarditis, heart failure, ventricular arrhythmias, embolic events, and rarely sudden cardiac death.

Beta blockers are the first-line treatment for symptomatic patients, especially for palpitations, chest pain, and anxiety-related symptoms.

Routine infective endocarditis prophylaxis is not recommended. It is indicated only in patients with a prior history of infective endocarditis or other high-risk cardiac conditions.

Surgery is indicated in patients with severe mitral regurgitation who are symptomatic, those with left ventricular dysfunction, or in selected asymptomatic patients with progressive cardiac changes.

The severity of mitral regurgitation is the most important determinant of prognosis. Patients without significant regurgitation generally have an excellent long-term outcome.

MCQ Test - Mitral Valve Prolapse Comprehensive Guide Symptoms Diagnosis Management MCQs

No MCQs available for this article.