Medical Disclaimer: This is educational content only, not medical advice. Consult a licensed healthcare provider for diagnosis/treatment. Information based on sources like WHO/CDC guidelines (last reviewed: 2026-02-13).

This article is being expanded for more depth. Check back soon!

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome Clinical Features Diagnosis and Management Guide

Frequently Asked Questions

Acute Respiratory Distress Syndrome is a severe form of acute hypoxemic respiratory failure caused by diffuse inflammatory injury to the alveolar–capillary membrane, leading to non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema, decreased lung compliance, and refractory hypoxemia.

The most common causes include sepsis (most frequent), severe pneumonia, aspiration of gastric contents, trauma, acute pancreatitis, massive blood transfusion (TRALI), inhalational injury, and near drowning.

ARDS is diagnosed using the Berlin criteria, which require acute onset within one week, bilateral pulmonary opacities on imaging, respiratory failure not explained by cardiac causes or fluid overload, and impaired oxygenation assessed by PaO2/FiO2 ratio with PEEP ≥5 cm H2O.

ARDS severity is classified based on PaO2/FiO2 ratio: mild (200–300), moderate (100–200), and severe (<100), all measured with PEEP ≥5 cm H2O.

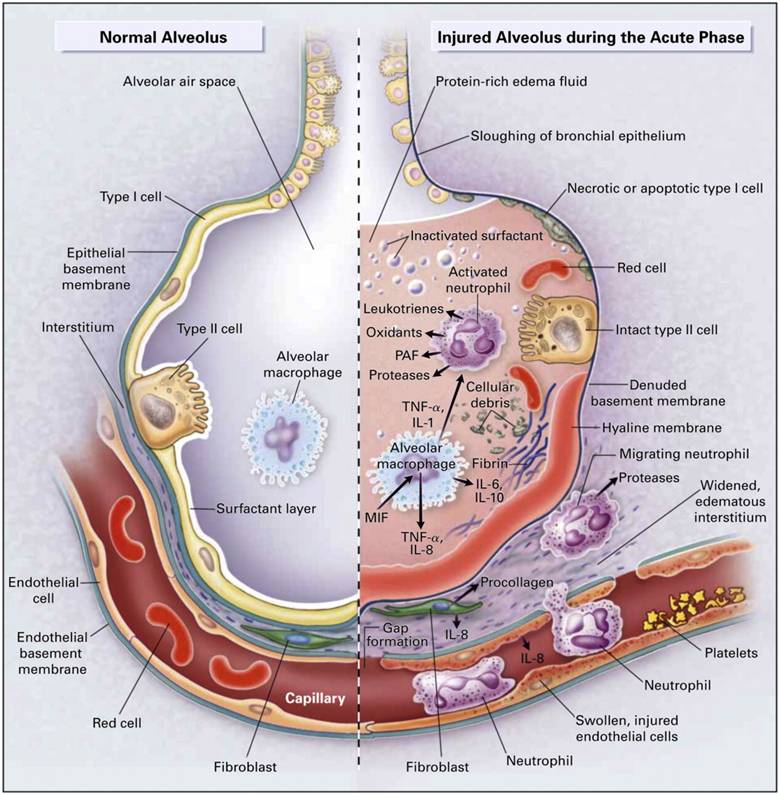

The hallmark is diffuse alveolar damage resulting in increased capillary permeability, protein-rich alveolar edema, surfactant dysfunction, alveolar collapse, ventilation–perfusion mismatch, and refractory hypoxemia.

ARDS is characterized by non-cardiogenic pulmonary edema with normal left ventricular filling pressures, whereas cardiogenic pulmonary edema results from heart failure with elevated cardiac filling pressures.

The cornerstone of ARDS management is lung-protective mechanical ventilation using low tidal volumes (6 mL/kg predicted body weight) and limiting plateau pressures to less than 30 cm H2O.

Low tidal volume ventilation reduces ventilator-induced lung injury, decreases alveolar overdistension, and has been proven to reduce mortality in ARDS patients.

Positive end-expiratory pressure prevents alveolar collapse, improves oxygenation, reduces shunt, and helps maintain functional residual capacity in ARDS.

Prone positioning is indicated in moderate to severe ARDS (PaO2/FiO2 <150) and should be applied for at least 16 hours per day to improve oxygenation and survival.

Yes, permissive hypercapnia is allowed to maintain lung-protective ventilation, provided there are no contraindications such as raised intracranial pressure or severe metabolic acidosis.

Short-term neuromuscular blockade may be used in early severe ARDS to improve ventilator synchrony, reduce oxygen consumption, and improve oxygenation.

Corticosteroids may be beneficial in early moderate to severe ARDS to reduce inflammation and duration of mechanical ventilation, though timing and patient selection are important.

A conservative fluid management strategy is recommended once shock has resolved, as it improves lung function and reduces ventilator days without increasing organ failure.

Extracorporeal membrane oxygenation should be considered in severe ARDS with refractory hypoxemia despite optimal lung-protective ventilation, prone positioning, and neuromuscular blockade.

Common complications include ventilator-associated pneumonia, barotrauma such as pneumothorax, multi-organ dysfunction, ICU-acquired weakness, and long-term pulmonary fibrosis.

The overall mortality rate ranges from 30 to 45 percent and increases with disease severity, advanced age, sepsis as the underlying cause, and presence of multi-organ failure.

Many patients recover good lung function, but some develop long-term sequelae such as reduced diffusion capacity, exercise intolerance, pulmonary fibrosis, and neurocognitive impairment.

Prevention includes early treatment of sepsis, lung-protective ventilation in all mechanically ventilated patients, aspiration precautions, judicious fluid therapy, and avoidance of unnecessary blood transfusions.

Severity of hypoxemia as measured by the PaO2/FiO2 ratio, along with the underlying cause and presence of multi-organ failure, are the most important prognostic factors.